Deferred Compensation Plans: Before the Agreements are Signed, Ensure HR and Finance are Aligned

As the talent war within the engineering and construction industry rages on, strategically designed deferred compensation plans can be decisive weapons for attracting and retaining key employees. Plans that feature meaningful mid-term (i.e. 3-5 years) payouts, for example, incentivize top players to endure beyond simply the next annual raise or bonus. When designing these plans, firms understandably tend to focus on the future cash flow impact. However, it is equally important to consider the plan’s effect on the balance sheet and income statement, as well. Under U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP), the structure of most deferred compensation plans will generate liabilities and expenses for the company long before any cash is distributed to the participants. The following guidance and example will provide a well-rounded perspective.

Guidance and Example

Under U.S. GAAP, deferred compensation costs are to be accrued at present value, in a systematic and rational manner, over the service period that entitles the employee to the compensation. The theory behind this accounting is that, while the compensation is not paid until a future date, the employee is earning the compensation in the meantime via the service they provide to the company. Given this guidance, the key drivers of deferred compensation financial statement implications include:

- The inputs used in determining the future payout, as specified in the agreement; common examples of inputs include employee salary, company performance metrics, and performance evaluation scores.

- The timing of the future payout.

- The service period tied to the future payout.

- The applicable discount rate: the company’s incremental borrowing rate is generally a reasonable figure to use when determining present value.

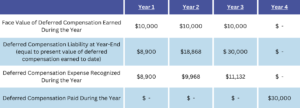

To illustrate these drivers via an example, let’s say that “Company A” executes a deferred compensation agreement in “Year 0” with key employee “Brett.” The agreement entitles Brett to a payout equal to 30% of Year 0’s salary on January 1st of “Year 4,” provided he is still employed with Company A on December 31st of “Year 3.” If Brett’s salary in Year 0 ends up being $100,000 in Year 0, this will drive a $30,000 payout on January 1st of Year 4. However, he must remain employed over the ensuing 3-year service period to earn this benefit. Assuming a discount rate of 6%, the following table illustrates how Company A would systematically and rationally recognize the deferred compensation costs associated with this agreement in Years 1, 2, and 3.

Key Takeaways

As the table above illustrates, the deferred compensation agreement impacts Company A’s financial statements significantly in Years 1, 2, and 3 in the form of liabilities and expenses, despite the physical payout not occurring until Year 4. Thus, when structuring deferred compensation plans, it is critical to model out the future cash outlays, as well as the timing of liabilities and expenses. Careful planning on the front-end will help to prevent any adverse financial surprises down the road.

Conclusion

While the accounting is important to understand, it is just one piece of the planning discussion. Here are some other key questions that companies should ask as they consider which deferred compensation plan designs best fit their objectives:

- Which time horizon do we want to reward: short-term, mid-term, or long-term? This answer may differ depending on the level and career stage of the individual.

- What will be the funding mechanism for future pay-outs? General company assets, separate investment accounts, and corporate-owned life insurance are common options worth consideration.

- Which future activities should we incentivize? Is it purely retention, or are there key performance-based metrics, as well?

- Are there certain non-compete or other qualitative provisions that make sense to include in the agreement?

By approaching plan design with firm answers to these questions, companies can ensure their future financial and succession planning strategies are well-aligned.

For more information about McKonly & Asbury’s Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) experience, visit the AEC industry page and don’t hesitate to contact a member of the AEC team.

About the Author

Tim is a leader within our Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) Practice, serving clients across the Mid-Atlantic. He also chairs the firm’s Technical Committee, which exercises oversight of the firm’s Assurance Segmen… Read more